“You’re getting too dark – stay out of the sun.”

Content Warning: The following piece is a personal journal entry by a Queer Pinay femme exploring internalized colourism rooted in Asian and Pacific Islander (API) communities, the beauty of brownness, and her thoughts and experiences around dismantling anti-blackness within herself.

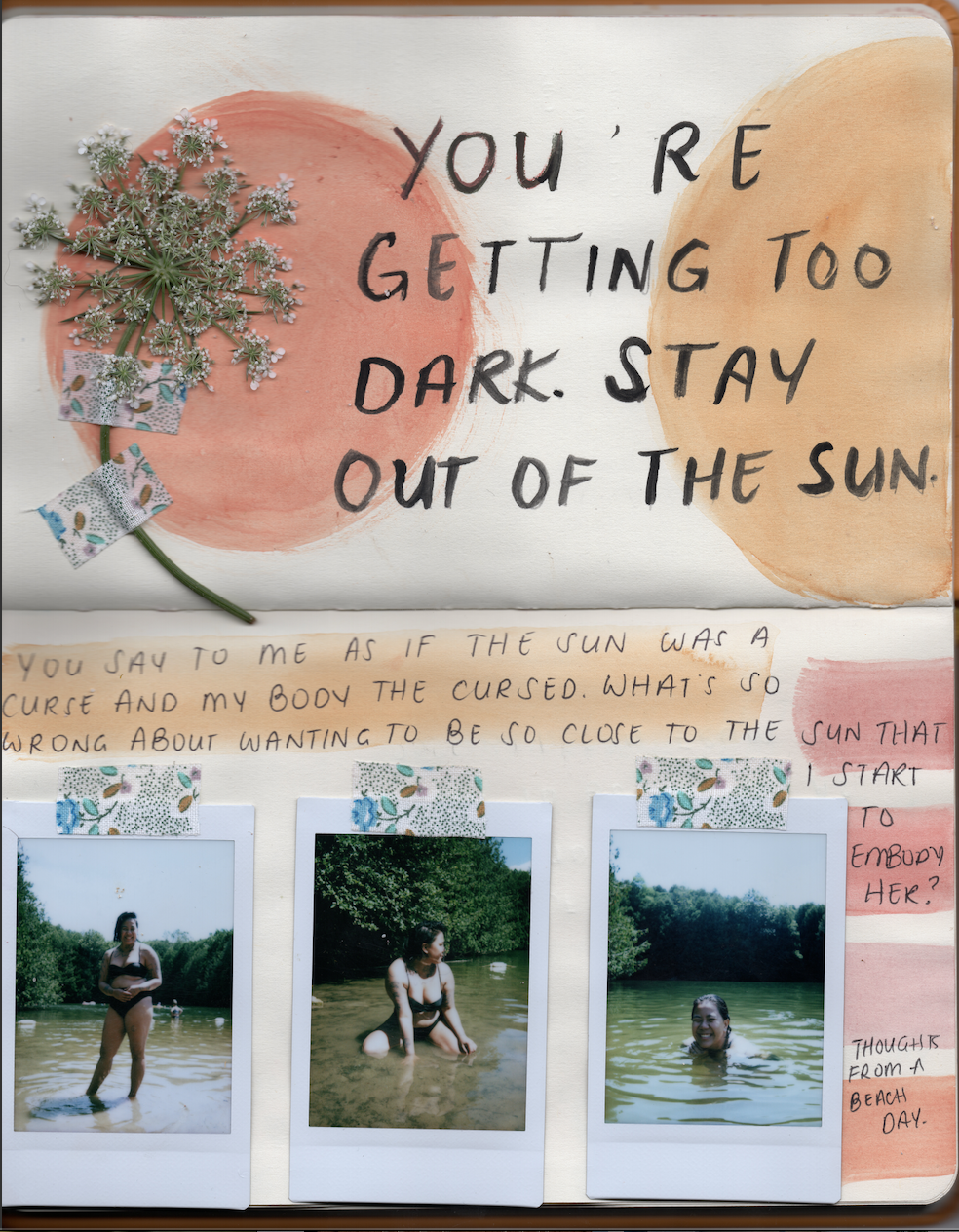

Pages from visual journal entry by Anna Balagtas.

“You’re getting too dark – stay out of the sun.”

You say to me as if the sun is a curse and my body, the cursed. What’s so wrong about wanting to be so close to the sun that I start to embody her?

Colourism has been ingrained in me generationally. It existed in my bones before they had even formed. I was born milky white because my melanin hadn’t set in, and I grew up getting darker and darker. My family would joke that I was an outsider to them. I would pretend like it didn’t hurt. On my mother’s side, they would say their skin was made of cream. And my father’s side, they would describe their skin as punong nasunog, like a tree that had been burnt and left with dark bark.

Last week I went camping with my best friend for a week. We had a beach day where all we did was alternate between swimming in the lake or sitting on our beach chairs reading in the sun. All I could think of the whole time we were out was how dark my skin was getting. I’m past the point of feeling shame for it now – not like the shame I felt when I was a kid – but it still lingered there. Like a hangnail. Like a thorn in my side.

Dr. Belo was a name I heard thrown around in my childhood. She’s a widely known Filipina dermatologist and celebrity who promotes skin whitening. She built her whole career around it. When I was in the Philippines, the colour of my skin never bothered me. Everyone around me had similar skin tones, and I never felt out of place. Skin-whitening creams, soaps, and cleansers were everywhere, though.

When I immigrated to Canada – that’s when I started to see my brownness differently. I wanted to be as close to whiteness as possible, to fit in like the white kids. Shame around being brown even trickled into the playground. The other Filipino kids, specifically the girls and I, would compare our skin tones because the whitest one would be the “leader”. When I saw that I was lighter than one of them, I would celebrate inside - as if achieving whiteness was a proud accomplishment. As if whiteness meant I would be a better leader. The colourism ran deep in me in those years.

I remember watching Filipino teleseryes with my mom on TFC or GMA, where the damsel in distress was always in likeness to someone like Marian Rivera, skin white and clear and always the victim. The villain? Someone darker skinned. Anti-blackness was rampant in the shows we watched, but when I was a kid, I didn't have the vernacular to call it as I see it now.

During this era of watching teleseryes, I stockpiled papaya soaps, ate papaya every day, and slathered papaya juice on my body because I remembered watching Filipino programming with my mom, where Dr. Belo claimed that papaya is good for skin whitening. Plus, I equated brownness to villainy and whiteness to heroines. Why wouldn’t I want to be the latter?

As a teenager, I stockpiled Pond’s whitening cream that I would sneakily buy from Chinatown. The cream would instantly whiten your skin because there was something tinted within the product, almost like foundation. Instant whitening felt like it would solve my problems. For a moment, I could pretend my skin was lighter than it was. My mom never liked me buying these products, but I noticed she would compliment my skin when I wore the cream. The messaging was so conflicting.

The skin whitening business is huge in Asia. In India, commercials for Pond’s skin lightening cream equivalent, Fair and Lovely, show a person’s skin getting 3x lighter and becoming considered “lovely” because their skin was now “fair.” Can you imagine the harmful messages kids are getting from commercials like these?

Whitening creams like this come from manufacturers like Unilever, L’Oreal, Johnson & Johnson, etc. It’s no surprise that the largest skincare companies influencing and upholding beauty standards in the mass market are white-owned and white-run. They’ve infiltrated their way so much deeper than just my community. They’ve infiltrated our skin. They’ve infiltrated our sense of shame. We are being exploited for the sake of white supremacist beauty standards.

When I learned how deeply colourism ran in my body and its ties to colonialism, I was in my early 20s. If you ask me, that was way too long for me to put the pieces together, but it wasn’t my fault. I experienced colourism before I was taught what it meant. It’s not like it’s on warning labels on the skin products you buy:

“WARNING: using Ponds whitening cream enables colourism and colonial standards of whiteness as beauty.”

No. It’s not like that.

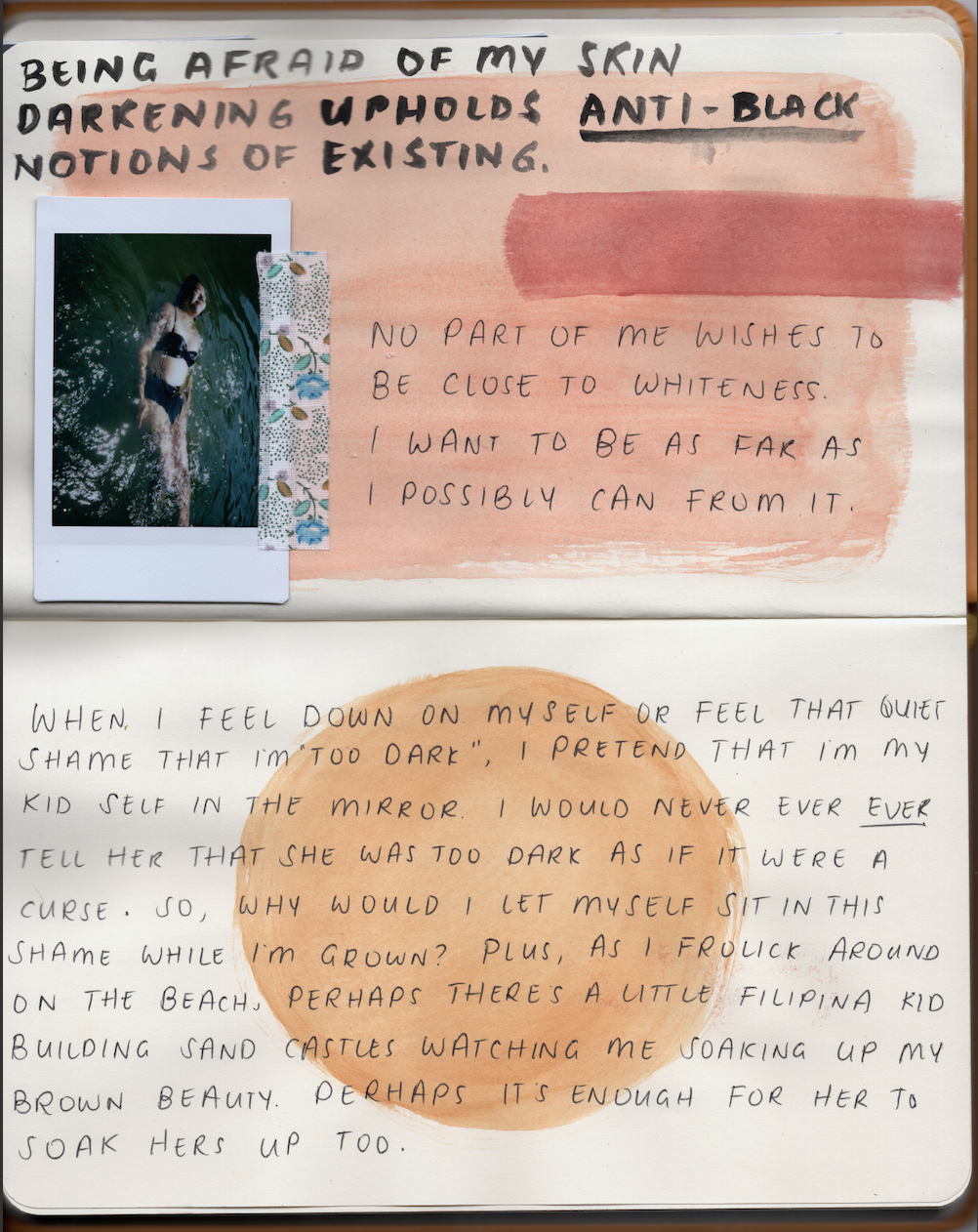

There’s still much dismantling I have to do to unwork my internalized colourism. But when I can, I stay in the sun for as long as I want and marvel at my skin. No part of me wishes to be close to whiteness. I want to be as far as I possibly can from it.

When I feel down on myself or feel quiet shame creeping in, telling me I’m too dark, I pretend I’m my kid self in the mirror. I would never ever tell her she was too dark – as if darkness was a curse. So, why would I let myself sit in this shame now that I’m grown?

Plus, as I frolic around on the beach, perhaps a little Filipina kid building sand castles is watching me soak up my brown beauty. Perhaps, it’s enough for her to soak hers up too.

That’s messaging I can live with.

About the Author

Kamusta! Ako si Anna Balagtas (she/they) and I'm a Queer + Pinay femme radical birthworker, educator, facilitator, and community organizer. I'm the founder of Pocket Doula and I support emerging careworkers in radicalizing their practice through heart-centered mentorships, facilitations, and community organizing. My practice is housed under the decolonization of birthwork and transformative queer care. My deepest joys come from witnessing our communities thrive through community care, mutual aid, and abolition work.